A new study’s findings “moved the needle” on researchers’ understanding of how ETI works. (Stock illustration)

The 2019 approval of the transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulator elexacaftor, ivacaftor, and tezacaftor (ETI) for cystic fibrosis (CF) dramatically changed the landscape of the disease. For the first time, nearly 90% of those with CF had access to a disease-modifying drug. In the pivotal clinical trial, ETI significantly improved lung function and reduced pulmonary exacerbations while improving patient quality of life.

But exactly how the drug worked still needed explaining.

Now, a major new study, called PROMISE, involving pediatric pulmonologist Spencer Poore, M.D., and University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) pulmonologist George M. Solomon, M.D., clearly demonstrates that some of ETI’s effects are due to its ability to tamp down inflammation.

Inflammation is the background noise of CF: always present, always active, contributing to lung damage, infections, fatigue, weight loss and poor outcomes. Even when symptoms improve, some degree of inflammation continues unchecked.

But as PROMISE showed, ETI dramatically reduces that inflammation. The PROMISE trial is a prospective, multi-center, observational study following 487 people ages 12 and older with CF. A group of 223 participants agreed to participate in the inflammation substudy, in which their blood and sputum were collected prior to starting ETI and then five times over the next 30 months.

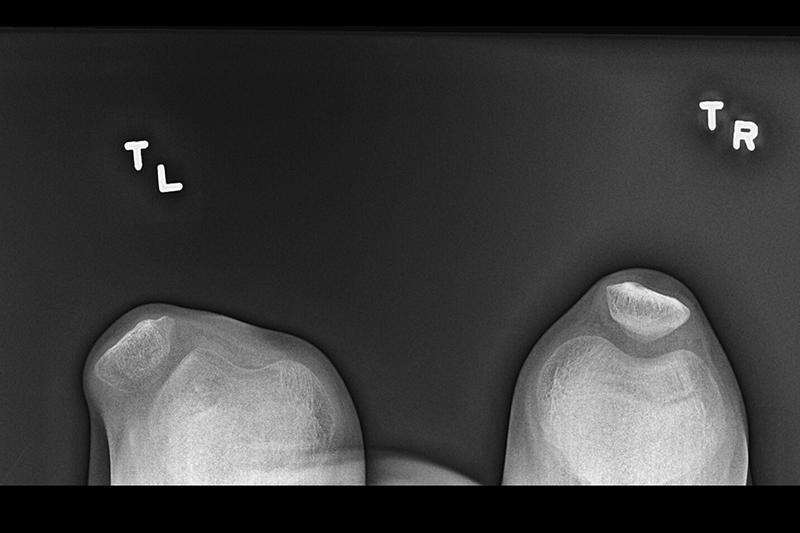

The team measured markers of inflammation in the lungs, including neutrophil elastase (NE), a powerful enzyme linked to tissue damage; calprotectin, a marker of neutrophilic inflammation; and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-8. In the blood, they tracked levels of the inflammatory markers high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP); calprotectin; and HMGB-1, another inflammatory mediator. All are tied to lung destruction, bronchiectasis, exacerbations and outcomes.

Within one month of starting ETI, airway inflammation markers fell sharply and remained low throughout the 30 months. At the same time, markers of system inflammation (hsCRP and calprotectin), also significantly declined.

As the authors wrote, “These changes represent a disease-modifying benefit of this transformative therapy.”

What made the findings even more powerful was how closely inflammation tracked with clinical outcomes. So, lower neutrophil elastase levels meant better lung function, while lower hsCRP led to improved respiratory symptoms. Interestingly, an increase in airway IL-6 also correlated with improved lung function, a puzzle since IL-6 is often thought of as inflammatory. However, the authors noted, it also plays a role in regulating inflammation. This suggests its increase may reflect a shift toward a more normal immune response rather than chronic destructive inflammation.

Although ETI quelled much of the inflammation, it was still there, especially in older patients and those with more advanced lung disease.

“We have not seen complete resolution,” Poore said. But, he noted, the set point has shifted. And this represents a shift in the disease itself, he said. “What I was taught versus what I see now is different.”

This includes fewer patient admissions; less dependence on feeding supplementation, advanced feeding support and feeding tubes; improved growth; and more stable disease.

One of the biggest questions lies with children who start therapy very early given that ETI is now approved for kids as young as 2.

If they never experience that chronic inflammatory engine, “what does their health and outcomes look like when they’re 25?” Poore asked. Does early treatment prevent the damage entirely? Or does it simply delay it? “We’ve moved the needle,” he said. “But how far?”

That uncertainty is fueling ongoing research. “This isn’t done,” he said. “This is a living, breathing assessment.”