In 2023, Children’s of Alabama performed deep brain stimulation on progressive dystonia patients for the first time.

Progressive dystonia disorders, characterized by changes in movement patterns, can profoundly impact a child’s quality of life. In adults, such disorders are routinely treated with a procedure called deep brain stimulation (DBS). However, this intervention is less commonly used in pediatric populations.

In 2023, Curtis Rozzelle, M.D., and Emily Gantz, M.D., performed Children’s of Alabama’s first DBS procedures for progressive dystonia patients. This innovative therapy has shown promising results in several pediatric patients with limited treatment options.

“We’re excited that this innovative procedure is now transferring over to our pediatric patients,” Rozzelle, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Children’s, said. “Kids with progressive dystonia seem to do particularly well, while those with other types of movement disorders may have mixed results.”

Studies suggest that pediatric patients with progressive dystonia respond well to deep brain stimulation, especially after failing conventional medications. The decision to apply DBS in pediatric cases stems from the specific needs of young patients and advancements in the field.

“Until Dr. Gantz arrived at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, we didn’t have a movement disorder neurologist here who also had training and experience with deep brain stimulation,” Rozzelle said. “When she arrived, Dr. Gantz opened the door for us to be able to perform the technical aspects of the surgical procedure. Now, we’ve done several.”

Not every child is an ideal candidate for DBS. The decision to initiate DBS is patient-specific, based on the severity of symptoms and the inadequacy of other treatments. A careful evaluation of each patient’s unique situation, including factors such as genetic mutations and the progression of the disease, must be completed before offering DBS surgery.

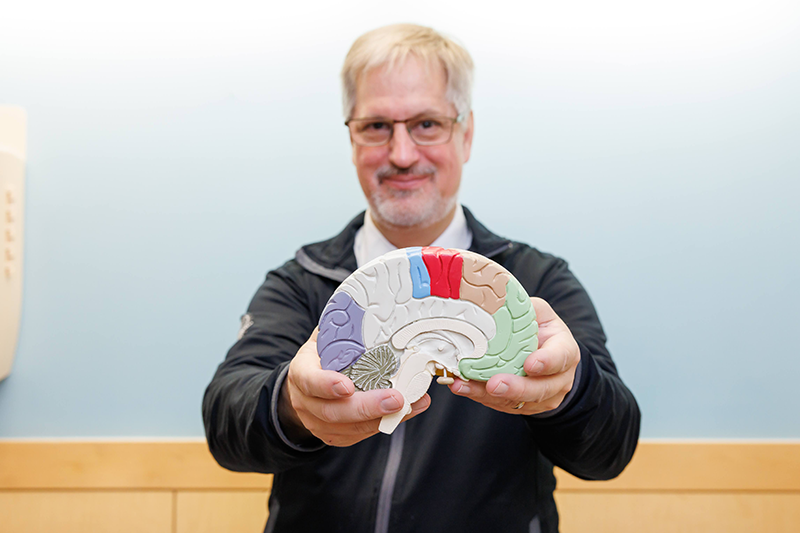

Each deep brain stimulation procedure at Children’s uses stereotactic surgical techniques and the ClearPoint targeting system. This system, employed in an MRI scanner, ensures safe, precise electrode placement in the globus pallidus interna (GPI), a key target for treating progressive dystonia.

“When we implant the electrode into a specific region of the brain, we can either edit the input throughout the stimulation, or we can take it completely away,” Gantz said. “Think of it as a series of relay circuits in the brain. If someone has dystonia, one of those relay circuits isn’t working properly. By putting in the stimulator and applying an electrical current intermittently, we can suppress the abnormal brain activity.

“The stimulator stays in for life, so the procedure doesn’t need to be repeated,” she continued. “Occasionally, we’ll have to change the device’s battery, but they’re rechargeable and designed to last for up to 20 years.”

After the initial procedure, patients return to see Gantz to have the device programmed. “I set the programming on their stimulator so they can make slight adjustments at home. It can take a little while for the device to be effective; we usually leave it alone for a few months and then reevaluate,” Gantz said. “We have guidelines for which settings will most likely help, and we start there. We’re looking to ensure we don’t get side effects, such as visual disturbances or muscle pulling, more than anything.”

The pediatric patients who have begun DBS for progressive dystonia at Children’s are responding well to the new treatment. “I’m really excited about DBS and its future as a treatment in pediatric neurology, specifically movement disorders,” Gantz said. “It may eventually come into play in other treatment areas, and I’m glad the door is open to us here. I think there will be many more patients who will benefit from it.”